|

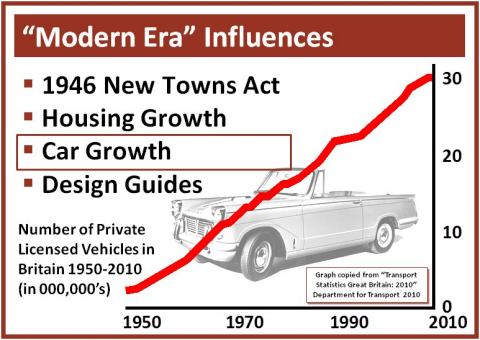

Widespread car use brings us to the modern era |

|

|

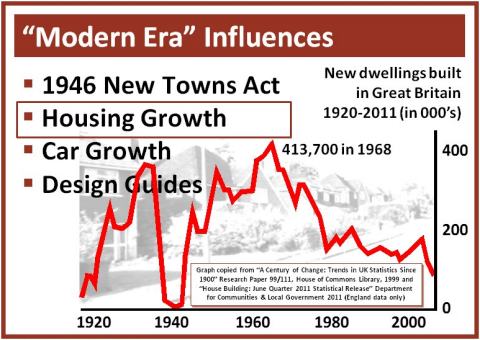

After the Second World War new house building took off again |

|

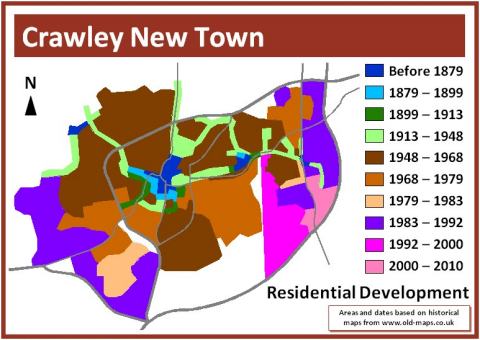

Within modern-day Crawley there were originally four villages or hamlets: (from west to east) Ifield, Crawley, Three Bridges and Pound Hill (the blue areas on the map) |

|

|

All governments between 1945 and 1971 actively encouraged house building with subsidies to developers and to councils to build more homes |

|

During this period the number of private licensed vehicles increased from 2.5 million in 1950 to just over 30 million in 2010 |

|

|

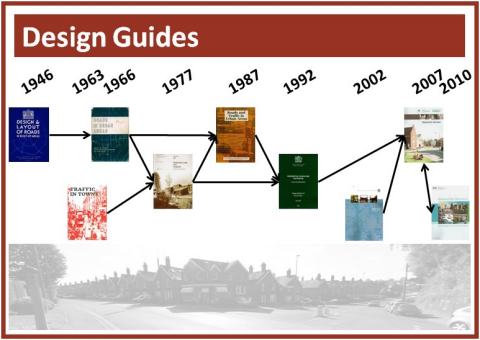

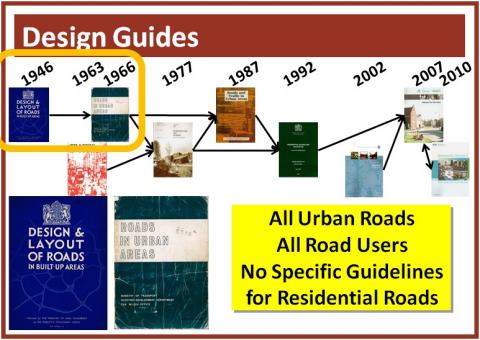

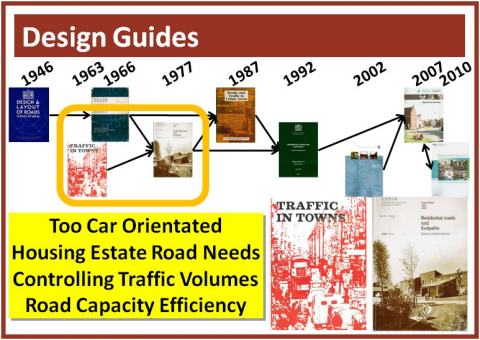

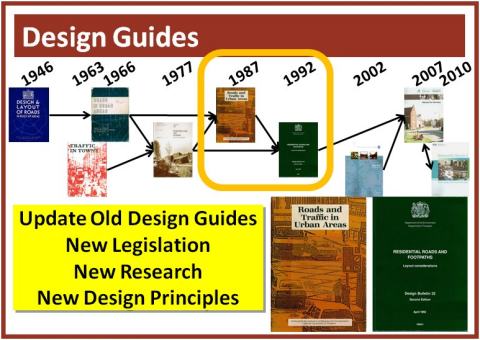

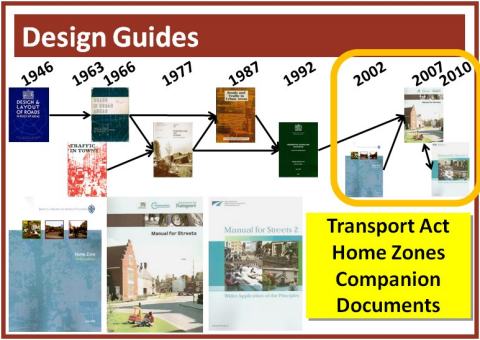

Here we have a flow chart showing a series of road design guides and documents from 1946 to 2010 |

|

The first two, "Design and Layout of Roads in Built-Up Areas" from 1946 and "Roads in Urban AreasĒ from 1966 covered all roads in urban areas |

|

|

The 1970s saw concerns that roads in new housing estates were too car orientated and didnít take into account local residentsí needs |

|

In 1987 "Roads and Traffic in Urban Areas" replaced "Roads in Urban Areas", and the second edition of DB32 came out in 1992 as the old documents needed updating to reflect new legislation, new research and new design principles |

|

|

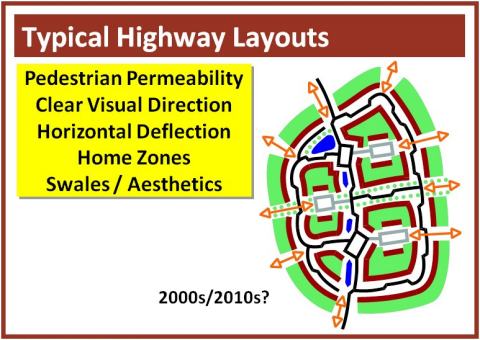

The Transport Act 2000 allowed local authorities to create Home Zones and the "Home Zone Design Guidelines" came out in 2002 |

|

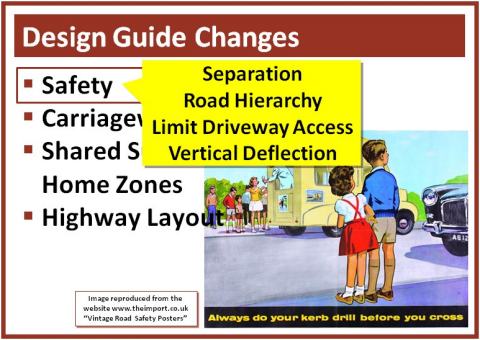

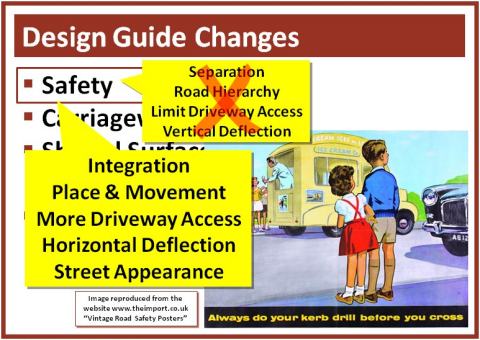

The primary concern in all the design guides is safety |

|

|

From the 1940s to the 1960s road design was car dominated and it was thought the safest way to protect pedestrians and cyclist from cars was to separate each type of road user |

|

In the last 10 to 15 years the focus has moved away from car dominance and now instead the pedestrianís needs are considered first. This is among a number of changes set out in Manual for Streets |

|

|

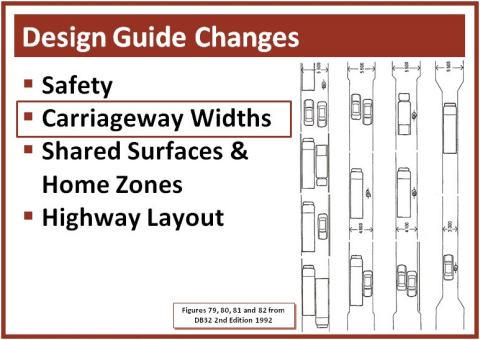

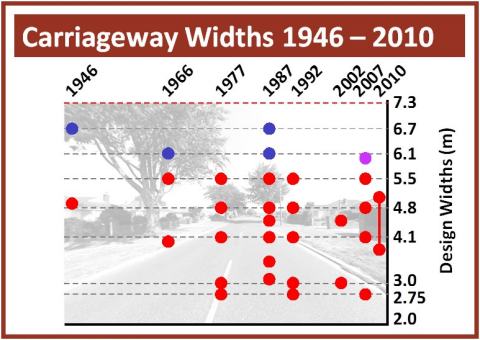

Itís interesting to see how carriageway widths are treated in the design guides |

|

The line across the top is the Victorian 7.3m (24 feet) wide Bye-Law Street. The blue circles represent all purpose roads, and the red circles represent residential roads |

|

|

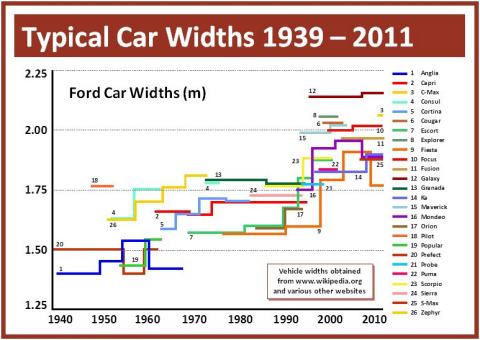

This graph shows widths for various Ford cars sold in the UK since 1939. Iíve chosen Ford because their cars have been popular for years. So changes in their design should reflect changes in the overall market |

|

The ideas behind Shared Surfaces and Home Zones are not completely new |

|

|

Shared surfaces are mentioned in DB32 and subsequent design guides. They are best used in cul-de-sacs or short loop roads, and can be applied to small road networks |

|

Home zones are a more recent implementation of a shared surface |

|

|

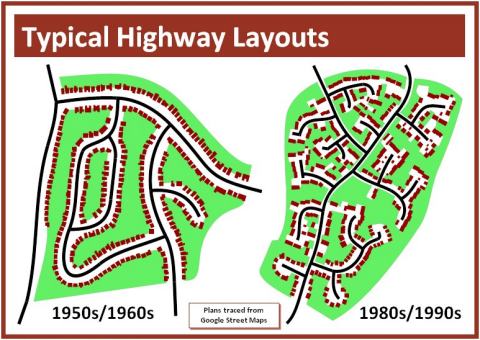

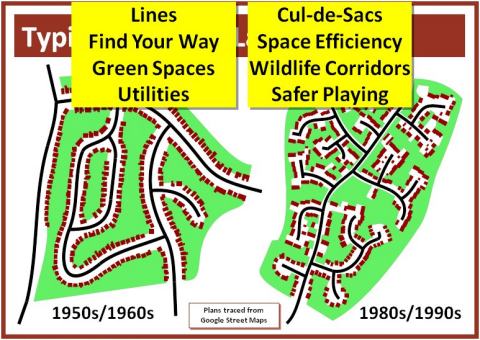

Finally itís interesting to compare how highway layouts in housing estates have changed over the past 60 years |

|

The most obvious difference is that the housing on the left is in lines along each side of each road while on the right it is more grouped in cul-de-sacs |

|

|

The latest layouts should consider pedestrian movements first. This site is very permeable and pedestrians can easily find their way round using direct routes, as the orange arrows show |

Even with all the changes over the past 60 years, there is skill scope for improvement. So what might happen in the Future?

| Contact Me Home Page | This page was last updated on 17th December 2012 |