|

At the other extreme the new wealthy class could afford to buy plots in new developments on the spacious edges of urban centres, and they would choose house designs from pattern books

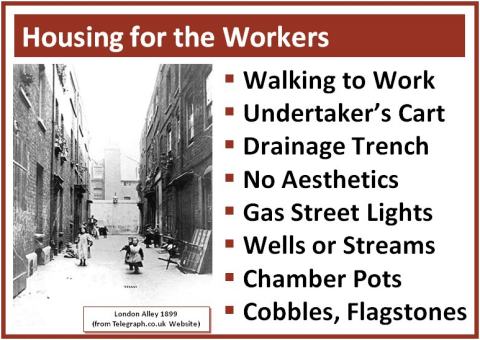

Looking at the "soft" design considerations the primary journey would, again, be getting to and from work – typically by private carriage or public transport

With more leisure time there would also be more non-work journeys, such as nannies with prams

For non-resident journeys, there were local deliveries from milkmen and butchers, and the new wealthy class were purchasing furniture and furnishings for the first time, which all needed delivering

So the roads needed to be wide enough for two-way horse-drawn traffic

This increased traffic also meant more horse manure and other waste in the carriageway. So a clear footway to one or both sides of the road was vital

For the "hard" design considerations these developments relied on their picturesque appeal to sell the plots. Therefore the roads were often laid out to provide "unfolding views" and mature trees and hedgerows were retained where possible

Early housing estates could be remote from drainage networks and services. So road drainage would be verges acting as soakaways, and individual houses would have cesspits and wells and use candle light

As cities expanded outwards and surrounded these early estates they would be connected into the new drainage networks and gas and water supplies

Marketing brochures and 19th century photographs show a variety of surfacing types. Some show verges and unpaved carriageways, others show footways paved with flagstones and cobbled or waterbound macadam carriageways |